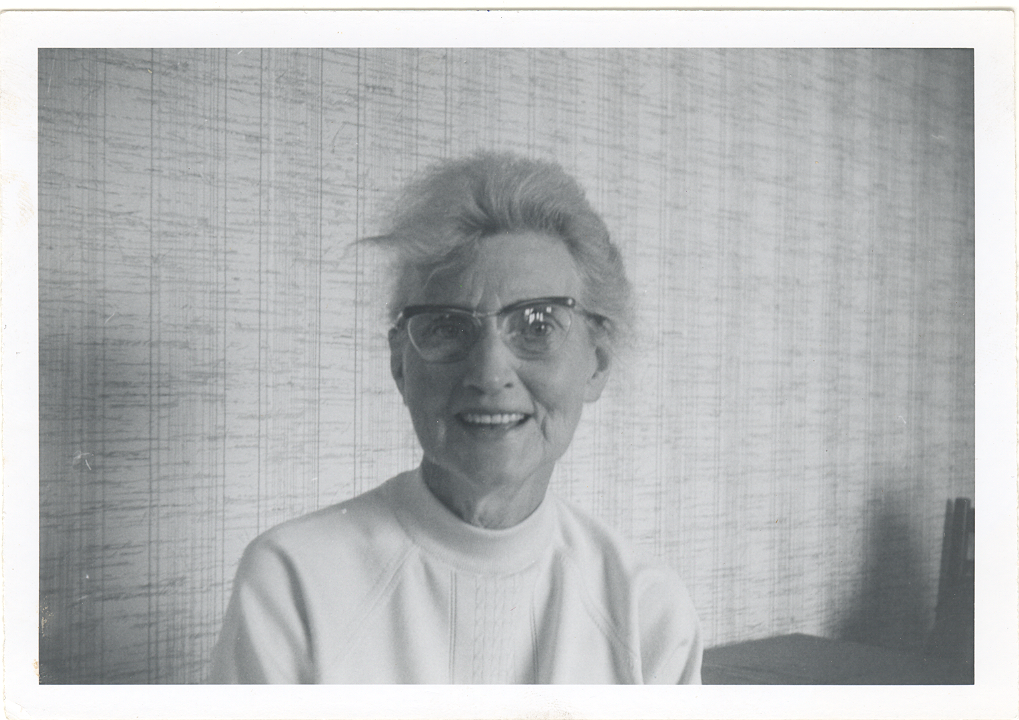

When I was in my pre-school year, for practical reasons my parents farmed me out to live with my grandmother on the other side of Omagh.

She had recently been widowed, her and my grandfather Hugh Friel having moved to a new bungalow on the edge of the town. There she lived with her cat Rascal, a beautiful and friendly cat that she found in the garage and kept for many years.

Staying with my granny had a longlasting effect upon me.

Every morning we walked the distance to mass in town. I look at my own children now and realise that I must have deeved her head talking rubbish, playing with my toys.

She always said I was very good. I had reason to be – every day she would buy me one thing in the shop. I knew not to ask for anything else.

At the weekend I would be returned to my family where I called my mother granny and my other brothers ‘Jimmy’ – my uncle’s name.

It was an idyllic time and whilst I cannot recall many of the specifics with the passing of the years, it is shrouded in a warm glow of happiness.

When I started in primary one, I used to wait after school in my uncle’s pub. There I would hang around and talk to the men in the bar. I am sure looking back that the only men drinking in a bar at lunchtime would have been fairly hard core locals, yet here I was shooting the breeze with them.

I remember these guys lowering pints, half ‘uns, nicotine covered fingers toking on endless fags. In those days pubs didn’t have televisions so these guys sat at the bar. And drank. And drank.

I enjoyed dipping my finger into the spill trays below the beer taps. A toastie machine appeared in the bar, a total novelty. The smell of toasted ham sandwiches mingled in the fugue with smoke from Benson and Hedges, Regal and the occasional bit of pipe tobacco. Occasionally I might be bought a bag of crips, Golden Wonder Smokey Bacon stick in my mind and maybe a bottle of Coke.

I would happily play round the place, passing time until I was picked up by my dad or my granny or whoever. My particular friend was one old guy Maxi Chisum who must have been kind to me. It remains another happy memory.

As I moved through school I continued to visit my granny, staying over with her, keeping her company. She was the person who told me my father had had a heart attack and was in hospital, I arrived home from school to this particular piece of news. I didn’t realise its import at the time. It was Mrs McGale that told me he was dead but that is a story for another day, maybe never.

As I grew older my granny was a constant presence. I used to visit her every Saturday evening after dodging about the town with my mate Brogy. I would then walk back in to Saturday evening mass and on homewards. She used to make me delicious home made pizza with a soda bread base. It was awesome stuff.

At that time I would have been playing football and hurling and she always took an interest in what I was at. I didn’t know at the time that she often took clippings from the paper of reports of matches I played in, and kept them – we found these years later after she died.

As she got older and her health deteriorated a couple of times, she had some sort of mini stroke and had to come and live with us. Although her and my mother were as thick as thieves, after a short while in the same house horns would lock.

My granny was a stubborn woman, and she had her own way of doing things. Being told what to do by her daughter didn’t please her and nothing would do her only to get back to her own house, her own place that she knew and where she felt comfortable.

Her mind remained alert and although another stroke had taken its toll, she would often regale me with tales of living in Donegal and Derry in the early years of the twentieth century. She told me of travelling to Derry, and gunfire being directed at the train. Born in 1901, this was highly likely. She recounted how my grandfather had courted her in Derry and how they ended up in Omagh running the Military Arms pub.

My mother was surprised and perhaps a little wounded that I was hearing all these tales, stories that she had maybe not shared with anyone else.

Eventually a major stroke totally incapacitated her and she was permanently located in Ward 12 in the Tyrone County Hospital. It was full of all sorts of human debris, old people in various command of their faculties. What a place to end up.

Amazingly she staged a bit of a recovery but one side of her body was in a permanent spasm and she was paralysed and very severely incapacitated.

With great effort my mother got her out of the hospital to spend a few days over Christmas with us. I remember the glint in her eye when she grabbed a glass of wine that wasn’t hers at Christmas dinner. She was determined to enjoy things while she could. It was difficult to take her back to hospital but there was nothing else could be done. In my mother’s case she had retired the previous summer but had spent her first year of retirement looking after her ailing mother.

Transferred eventually to the General Hospital in Omagh, she seemed to lose heart. She would have known the General as the Workhouse, to a woman of her age and her vintage, whose own mother lived to the age of 99 and whose grandparents survived the Great Famine, it would have held a certain dread. It was there that I sensed her spirit start to dwindle. It coincided with my first year at University and after acting the candyman during the week I would return to visit the woman who had half reared me in her own gentle way.

In early June, she deteriorated badly and although I had visited, for some reason I had an irresistable calling urge to go and see her again. I called my friend Conor and asked him could he take me to the hospital, my mother already there. When I walked in she was there, lying in her hospital bed, behind the curtain, breathing in a shallow way, her eyes closed, unconscious. My mother said to me, maybe if you speak to her she will come around a bit.

Looking at her, I knew that was not something she would have wanted me to do. It was her time. Touching her hand, I said my own goodbye and let her go. I was happy to have been there to do that. I didn’t know what had drawn me to the hospital, but something did. I quietly left and went home, my heart breaking. I knew it was only matter of time before she slipped away. My mother returned a short time later with the news.